ECCV 2016

What’s Missing From Deep Learning?

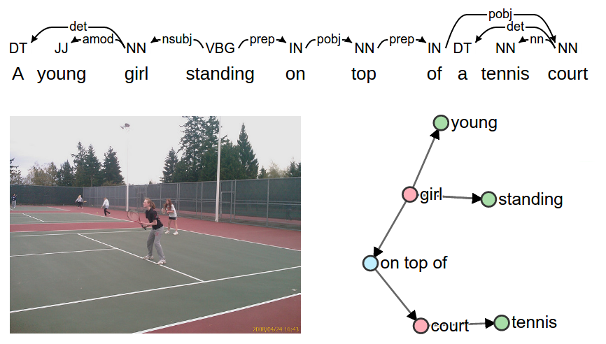

I recently had the privilege of attending ECCV 2016 to present our SPICE metric for image captioning. It was a great conference, with a friendly atmosphere and lots of exciting ideas presented. ANU and the ACRV were well represented, so congrats to all authors and prizewinners. According to the organizers, deep learning was the single largest subject area at the conference, in terms of both submitted and accepted papers. With this field still enjoying enormous success, it’s interesting to ask ‘what’s missing from deep learning?’. Let’s dive into some of the conference highlights that touched on this issue.

Slow Inference, Prior Knowledge and Uncertainty

Max Welling gave a very interesting invited talk at the workshop on Brave New Ideas For Motion Representations co-organized by Basura Fernando. He outlined his view of some of the high-level challenges facing deep learning, such as:

- Figuring out how to do slow inference, rather than just fast feed-forward inference. The distinction sounded a bit like the two mechanisms of the human mind described in Thinking, Fast and Slow. For example, slow inference might mean reasoning about future actions or causal relations.

- How to encode prior knowledge — such as the laws of physics — into a deep model, for both data efficiency and robustness to domain shift.

- How to generate better uncertainty estimates, for real-world deployments and reinforcement learning.

Many of these issues have also come up in discussions around the ACRV, so clearly there is a lot of interest in tackling these limitations.

Data

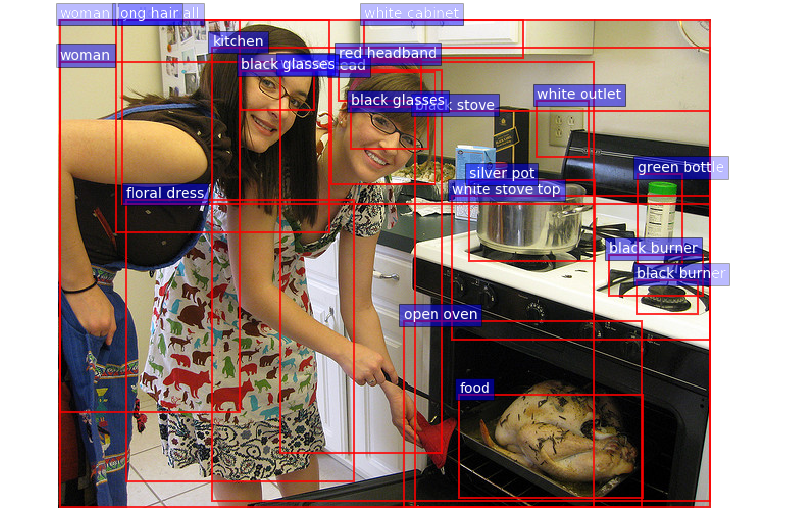

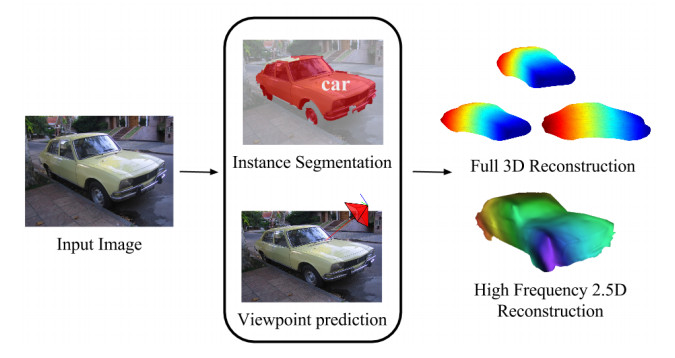

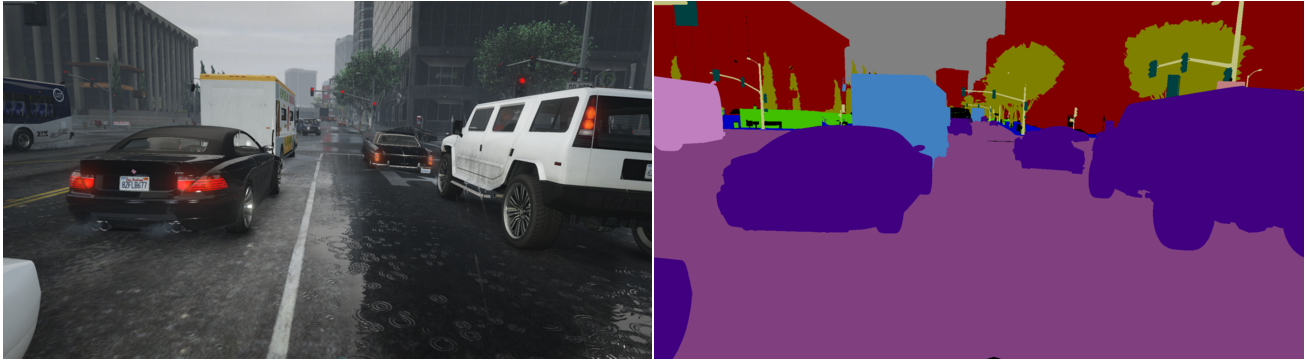

It’s well known that deep neural networks generally need large datasets to reach maximum performance. However, lot’s of data costs lots of money, especially if the data annotations are time consuming to produce, such as bounding boxes or image segmentations. In Playing for Data: Ground Truth from Computer Games, the authors circumvent this issue by harvesting large-scale pixel-accurate segmentation ground truth data from GTA 5. The use of commercial video games overcomes the issue of populating open-source graphics simulators with 3D assets. The key idea in this paper is that, even without full access to the game content, objects can be segmented by intercepting their polygon meshes. Annotations can also be propagated across frames. Neat.

Also addressing the data issue, but in a completely different way, Vittorio Ferrari gave an interesting keynote at the ImageNet and COCO Visual Recognition Workshop on learning object detectors without bounding boxes. Suppose you have a fixed budget for data annotations. How should you spend it? It turns out that it is much more efficient to use human’s to verify bounding boxes, rather than to draw them.

Efficiency

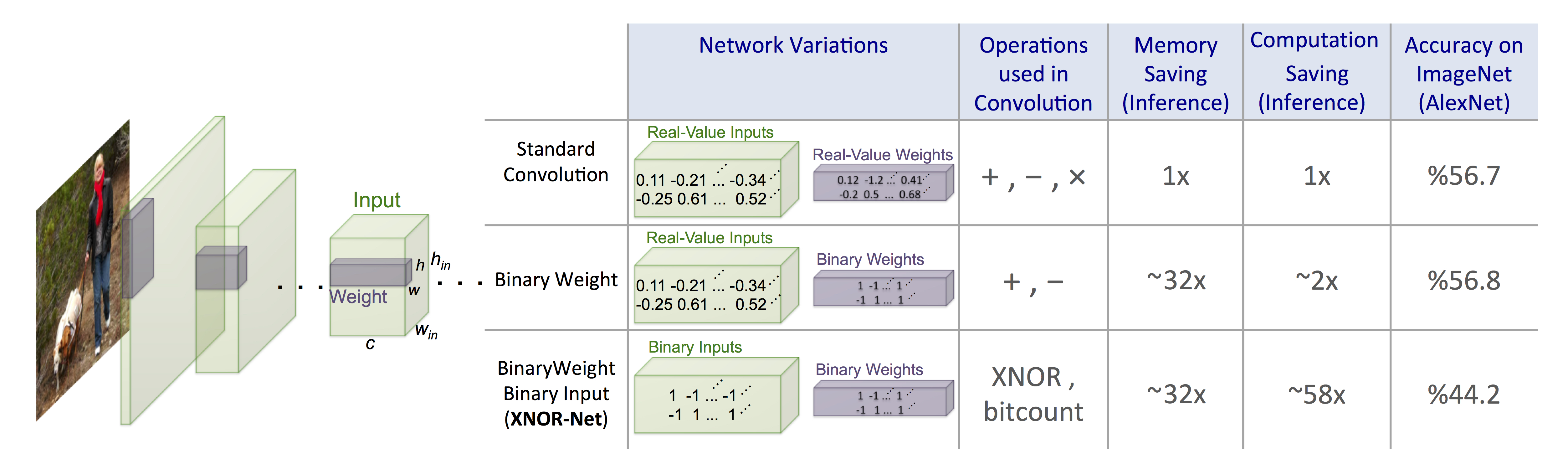

In recent years, we have seen binary codes used successfully for both low-level image descriptors (e.g. FREAK, BRIEF) and high-level semantic image representations (e.g. binary hashing for image retrieval). Binary codes have the advantage of maximising the information carried by each bit, achieving greater memory efficiency over floating point representations that waste bits describing the nth decimal place. So it’s really exciting to see binary codes finding their way into the intermediate layers of a neural net. In XNOR-Net: ImageNet Classification Using Binary Convolutional Neural Networks, both the convolutional filters and the feature representations are binary, resulting in massive memory and computation savings. While the full binary XNOR-Net does sacrifice accuracy, it seems to be a very promising research direction.

Design Patterns

At a high level, it seems like a lot of papers were presenting new or modified deep learning architectures, demonstrating improved performance for particular tasks. My question is, which of these ideas will turn out to flexible, elegant and reusable designs? I look forward to the day when some of the giants in the field will catalog all this accumulated wisdom and experience into a concise book on Deep Learning Design Patterns, similar to the original classic book on reusable software engineering by the ‘Gang of Four’.

For example: when should we use a neural attention mechanism? Or a memory network? What are the consequences and trade-offs of using it? What are the alternatives? I think the answers are still a few years away.

Network Description Language

Having spent a good week listening to ECCV presentations and reading papers, I can’t help but feel we have moved way beyond the capacity of current formats — block diagrams, supported by equations and text — to adequately describe the complex deep learning architectures that people are using now. For want of a better term, I would say the deep learning community is missing a Network Description Language (NDL) — a standard language to describe the structure and training / inference procedure of neural network architectures. Standardization may seem boring, but I suspect it would be incredibily handy if networks could be accurately described, and ultimately, designed, without being tied to a particular software framework such as Caffe or TensorFlow. Code releases are good, but given the number of different deep learning frameworks around — including proprietary ones — code releases are only part of the answer. I’m sure it’s no accident that the digital circuit design ecosystem revolves around two standard Hardware Description Languages, with a bunch of tools to synthesize to different implementation technologies. I bet we could borrow a lot of good ideas from existing data-flow languages such as VHDL and Verilog. There are already tools to convert nets between different deep learning frameworks, but no standard network description.

Edit: I hear you saying, isn’t Caffe’s protobuf network specification equivalent to a Network Description Language? The answer is no. Caffe’s protobuf format references Caffe layers, so it is tied to the Caffe implementation. If I change the ‘Convolution’ layer in the Caffe source, the protobuf now means something different. The other issue with this approach is that there is no way to specify a new type of layer or network component in protobuf. Also, protobuf is way too verbose. For example, the 152-layer Residual Net is nearly 7000 lines. A good Network Description Language needs variables and loops to specify repeated structure in a much more concise way. I wonder if the big players like Facebook, Microsoft and Google would ever work together on a Network Description Language?

What else is missing from deep learning?